CAREFUL attention to management and disease control is enabling a Welsh broiler producer to reduce antibiotic use in his intensive indoor system.

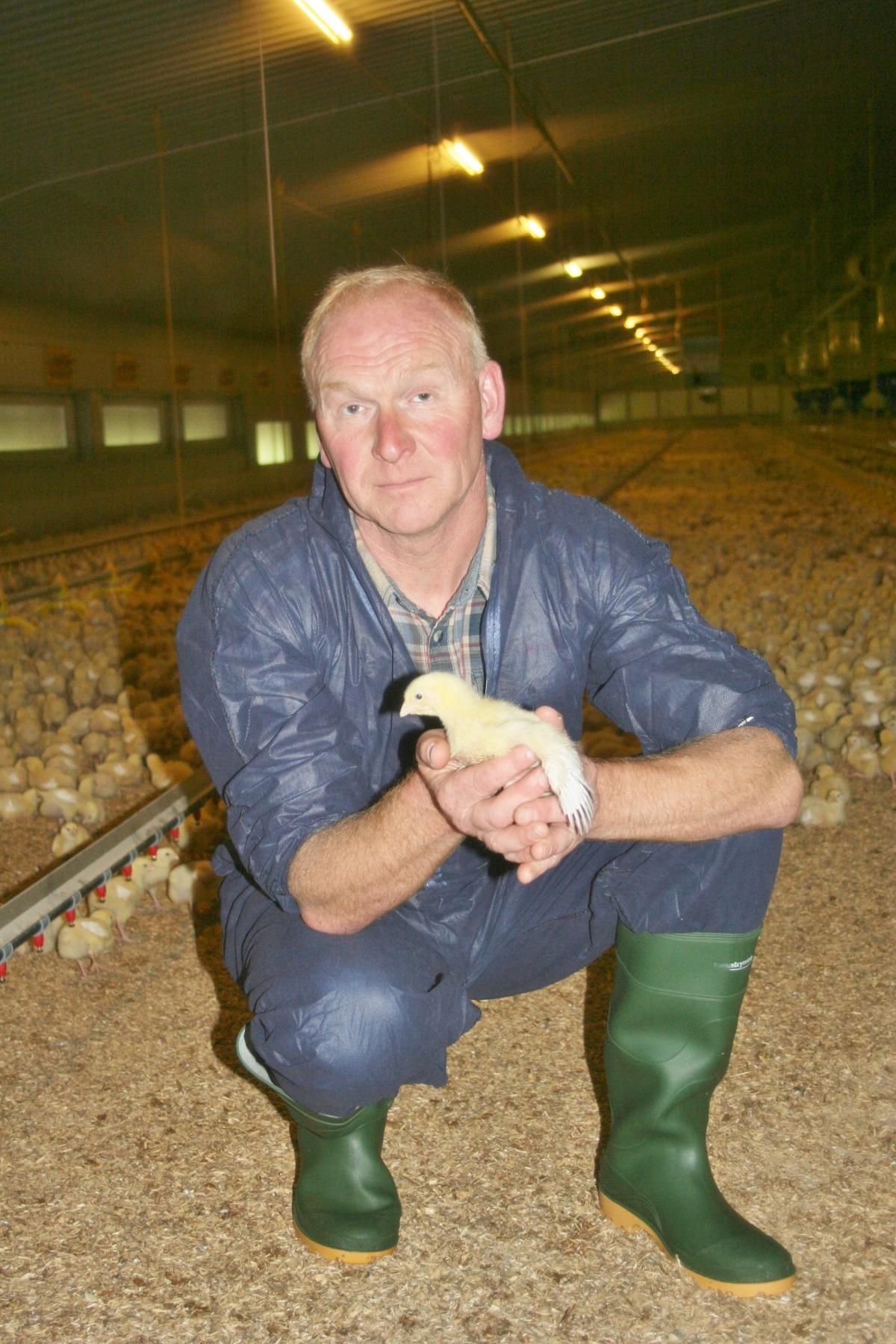

Ian Williams, NFU Cymru vice chairman for Monmouthshire, produces 1.4 million chickens a year at Llwyn y Gaer Farm, near Usk.

His family had been running the farm as a dairy unit, milking 120 pedigree Friesian Holsteins, but they sold the herd 11 years ago when the system came unprofitable.

At that time, they had also been running a turkey rearing enterprise but 12 years ago they switched to broilers. “The turkey market had been predicted to take off but it never quite captured the public’s imagination. Demand was stagnant and as a consequence the price started to stagnate too,’’ Ian recalls.

Ian estimates that he has invested around £1.75 million in the poultry business. Purpose-built sheds were established over a number of years, to the current six, which allows capacity for 200,000 birds at any one time. Those numbers are sufficient to allow Ian to employ a fulltime manager, John McGeen.

The business is run to Assured Chicken Production standards and audited annually.

It takes 41 days to grow the broilers, which arrive on the farm as day-old chicks and are slaughtered at between 2.3kg and 2.7kg liveweight.

Ian grow the birds – which are all Ross breed - on contract for Faccenda. The company has its own mills and supplies Ian with feed rations. He says this integrated approach takes the peaks and troughs out of prices. “There would be a significant cost for the chicks and the feed but we don’t have to find that money, the cost is deducted from our income.’’

When the birds are 10 days old, wheat is fed at a rate of 5%, rising to 30% at 38 days.

The poultry houses are open sheds, on a single level, with shavings on the floor and automatic feed and water systems. The shed is illuminated with strip lighting and the birds have six hours of darkness at night. There are windows which allow natural light into the shed.

The sheds are heated by two 198kw biomass boilers that were installed two years ago.

There is a seven-day turnaround between each group of poultry. Every batch produces approximately 250 tonnes of manure which Ian uses to fertilise his 340 acres of arable crops – wheat, barley, oats, beans and oil seed rape – and he sells what he can’t use to local arable farmers.

Llwyn-y-Gaer is a tenanted farm but the Williams’s own the 50 acres of land on which the poultry unit and his mother’s house stand.

The unit was built without grant funding but, had Ian been building it today, he may have applied for a Sustainable Production Grant. However he has concerns that this scheme will not benefit enough farmers.

“I think the Sustainable Production Grant should be available to a far wider spread of farmers, at the end of the day it is their 15% that has been taken away from their direct payments to fund this.

“The amount of money farmers must spend to get money back from the scheme is too high, that threshold needs to be a lot lower to allow more farmers to use it to make their businesses more profitable.’’

Ian is pleased he made the transition from dairying to poultry but admits there are similarities.

“There has to be someone within 10 minutes of the shed in case the alarms go off so it is quite a tie. But there is good cashflow because, if everything goes to plan, there is a cheque coming in every seven weeks.’’

There has been less volatility in poultry than dairying, he says.

“The sector has stayed reasonably profitable. We have no direct subsidies like other types of food production, we have had to stand on our own two feet.’’

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here